Petite Balade Alpine

Alpine Connections was the name of the WhatsApp group I had with some friends who helped me during this journey across the Alps linking summits over 4000 metres. It was somewhat ironic because I believe what I did was not important as such, but it was something that transformed me deeply.

Before my memory gets blurry, I wanted to write what this journey has been like while it is fresh in my mind. I know that at this point there are many things I need to reflect on and assimilate. I will be in the shadow of this traverse for a long time and will need a long period of assimilation and reflection. There will be probably a nice film when all these reflections are over, in which we can enjoy the beautiful pictures taken by the team, but here are some initial thoughts and things I take away with me, and some shitty pictures I took with my phone during those days:

- It was an inner journey, a quest to discover who I am, my motivations, fears, and limits. The 4000ers. The 82 peaks. They were the excuse, the framework that allowed this journey to unfold.

- To speak of records would cheapen the experience I had. I was deeply inspired by Patrick Berhault’s vision, by Martin Moran and Simon Jenkins’ first link-up of 4000ers, by Franz and Diego’s, and Ueli’s feats. But although we followed similar principles, we weren’t trying to break records. Instead, we wanted to explore the Alps linking those summits under our own power, not focussing on external performance.

- The connections are physical, rooted in the aesthetics of the routes, in the idea that once I reached a mountain range, I would stay up there linking summits and not descend, moving continuously or resting in refuges or bivouacs until all the peaks were linked before moving on to another range. That was broken in Valais, where a snowstorm happened and I went to check the conditions and did the Nadelgrat and went back down to Saas-Fee before continuing the next day. I then did a 4-day push to Zinal.

- The connections are also human. It was great to share the journey with friends, both old and new, who joined me for short or long sections. Thank you Philipp, Matheo, Genis, Noa, Michel, Bastien, Jordi, Jules, Leo, Emily and Benjamin. I am also grateful to the refuges for the warm welcome, bed and food, even late at night – Finsteraarhorn hut, Monterosa hut, Capana Margherita, Hornlihute, Rifugio Aosta, Cabanne de la Dent Blanche, Schönbiel hut, Tracuit, Valsorey, Rifugio Torino, Refuge de Couvercle, Rifugio Monzino, Camping della Sorgente, and Vitorio Emmanuele. And also a big thank you to the support team who followed the entire journey, to bring me what I needed in the valleys and record the journey. Thank you Aina, my mom, David, Joel, Nick and those who joined for a few days. Also, Jesús and Sergi for looking into what was happening inside my body during the trip.

- I made decisions I’m not proud of, which I need to review. That made me reflect on why sometimes I pushed too far, accepting some risks that I consciously find unreasonable.

- Physiologically, I managed well. I didn’t lose weight, unlike in the Pyrenees, where the physical decline was constant. Here, I was able to recover and finish strong. Eating well and, specifically, “resting” were crucial. Thank you Jesús and Sergi for all your advice about that!

- I flowed; on some ridges I didn’t feel the strain. I felt a deep connection with the mountain. Effort didn’t exist anymore, time stopped, my body was at one with the environment. Those are the moments I live for.

- It’s been 8 years since I left the Alps after living there for about a decade, and I was shaken by the changes in these peaks and glaciers. The effects of climate change on glacier loss and permafrost melting are huge. The routes have changed, the conditions have become more dangerous, the mountains are literally falling down. Here you can see some of the changes and the scientific explanations for it.

- To keep moving, no matter the conditions, weather or gear I had with me, I had to push myself to the absolute limit of my knowledge and beyond to make it through. The effort was physical, technical, but above all mental, in managing stress and emotions. The most difficult part of such a journey was to stay fully concentrated for so many hours a day and to lower the stress in complicated situations, to stay lucid and take good decisions and not spend more energy.

- I witnessed breathtaking sunsets, full-moon nights, and crimson sunrises. I touched magnificent rocks that made me dance with them to progress. I experienced long, magnificent hours of solitude and shared laughter and ridges with friends. In the end, it’s these moments that will remain.

The idea and planning

After last year’s Pyrenees 3000s traverse (click here to watch "Into the (Un)known, and see where I got the inspiration for this project). I was very taken by what I had experienced and it opened me up to exploring more in this direction. Back home it didn’t take long to imagine what I wanted to try. The Alps are a mountain range I’m familiar with after living there for a decade. It isn’t far so it doesn’t involve much travel and it offers great possibilities for link-ups in technical terrain. In the past I had done and imagined some long link-ups in different ranges there, so why not to do one big link-up encompassing all of them?

In the past I read about Berhault’s project, Moran and Nicolini’s books and followed Ueli during their traverses. And although the framework was the same (to climb all 82 4000ers under human power), I wanted to do it in a way that felt more like a long “non-stop” link-up than a multi-ascent collection link-up. So it was more to find a logical track inside each range. When I entered a mountain range, I would find a ridge or a route that linked all the summits on the range without the need to go down outside the mountains before linking all the summits and moving on to the next range. The aesthetics of it was what interested me the most, and although I realised that the chances of making it possible were low due to weather, conditions, and physical and technical capabilities, I wanted to try.

I started designing the routes of the ranges I knew best –Mont Blanc and Valais– then 4 ranges with isolated summits –Bernina, Weissmies, Grand Combin, which I didn’t know, and Grand Paradisso and Ecrins, which I did– and another big range that I had never been to before, the Bernesse Alps. After thinking of a track I thought doable I reached out to some friends, and friends of friends, to see what they thought of some parts. Andy Steindl, François Cazzanelli, Mitch Lanne, Philipp Brugger and Nicolas Hojac gave me their input and I had a basic route to start with. I then tried to find the topos of most of the routes of the traverse. In total, I added more than 150 climbing routes to do, some easy and some harder, with some sections in between with not much information and some that would definitely have poor conditions at that time of year. Although I had a plan with an “A” route and some possible timings, it was important to expect and be prepared for many changes. I had to be ready to improvise and find different solutions (alternative routes, places to stop, techniques to continue in different conditions, etc.) on the spot when weather or mountain conditions were not as expected.

Since we were planning to travel down to the Alps for Sierre Zinal with the family, I thought that the best thing would be to start some time after the race, to wait for a forecast that seemed reasonable and then go. I thought –and think– that with a perfect forecast and conditions it would be possible to do it in about 2 weeks. Doing it this late in the year had some advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand, the glaciers are pretty dry, which makes crevasses visible and less dangerous in terms of falling in or breaking snow bridges. The rocky ridges would be dry, making for faster progress. But on the other hand, being that dry makes bergschrunds more difficult to cross and rocks in the faces more unstable and so more dangerous.

Gear

First, gear itself doesn’t do shit. It’s knowing how to use the gear and how comfortable it is that makes gear useful or useless.

- Shoes: I used Tomir 2 shoes. 3 pairs. Most days I used Tomir 2 waterproof from day 1 till Torino hut after Droites (day 16). I used a pair of Tomir 2 non-waterproof on Nadelgraat so the waterproof ones could dry. From Torino hut I changed to another pair of Tomir 2 (non-waterproof) for the last 4 days. The waterproof ones were basically done (flat sole and some rips in the upper from the crampons and rocks). These are soft shoes that are good for running, walking and climbing in adherence technique but they require a good ankle and 10 pointes technique when ice climbing with crampons. They also need a different technique when climbing on rock compared with mountain boots.

- Clothes: from bottom to top, I used NNormal socks or waterproof socks depending the stages, a pair of tights or a pair of active trousers, depending the day. I also had waterproof trousers just in case. A merino t-shirt, a midlayer jacket, a windbreaker, a rain jacket, and a down jacket. Buff and hat. I used climbing gloves (fake leather) most of the time to protect my hands from rock abrasion. I wore 4 pairs during the trip. I also had a pair of gaiters I used in stage 3.

- For sun protection I used sunglasses (I had 2 cat 4 glasses) and suncream for my lips and face.

- For my protection and progression I had a helmet, a light harness, an ice screw, 2 ice axes (I used one at a time but, depending the stage, I would take a carbon ice & rock or a Grivel Ghost Tech), a pair of trail running poles, a pair of crampons (to fit the shoes well, I used a Petzl Lynx base with a Grivel soft front fixation, an Edelrid back soft fixation and a Petzl string). For some stages I used spike chains instead of crampons (Bernina and Gran Paradisso), 1 safety carabiner, 1 string and 1 carabiner, some cordelette, rope (I had a 40m x 5mm pure Dyneema and a 60m x 5mm Beal rad line, depending on the stage), 1 ice screw (Blue Ice 10cm) and an Abalakov hook, plus 2 cams (BD 0.4 and 1).

- For the night I had a headlamp, a Moonlight 2000, and always carried a spare battery.

- For tracking and communication I had a phone with the maps, a Coros Vertix, a tracking device, a GoPro, a power bank with a cable, and some money for the huts.

- For food and hydration I had 2 Softflasks and carried some food for the stage.

- To carry it all I had a 25-30L Prototype backpack.

In addition, I had a bike kit for the transitions, with a road bike (Wilier Vertical), shoes, helmet, bike clothes and a Coros Dura.

The team

Although it was a self-powered journey, I was assisted. Aina, who has been with me in numerous projects from the Himalayas to the Pyrenees was leading the team. She made sure I had food and a place to sleep, and managed the film crew. Nuria, my mother, was also there. The first week she stayed with Emelie and our daughters in Valais and then she followed with Aina. David Ariño, Joel Badia and Nick Danielson came to capture the journey on film. At the end, Noa Barraw, a friend of Matheo Jacquemoud’s, also joined for the last stages to film in the mountains too. For the first 10 days Jesus Alvarez-Herms and Sergi Cinca followed to take physiological and cognitive measurements when I was going down in between mountain ranges to study the effects of these extreme events. Other people came to help some days, including Anouchka, Sofia, Joan and Andreu. I also called a few friends to see if they wanted to share part of the journey.

The Journey

After Sierre Zinal I took a rest day and drove to St. Moritz. My legs were still a bit sore but muscular soreness doesn’t last more than around 70 hours, so I wasn’t worried. On Monday, 12 August, I prepared the gear and had a good night’s sleep.

Stage 1: Bernina

I meet Philipp Brugger at Mortetatsh station at around 5am. It had been a long time since we had seen each other so it was nice to catch up, talk about our kids and family, and enjoy the climb up to Bernina via Spalla ridge. It’s a nice route, very varied and with no complications. The weather was perfect, sun and no wind, and we were able to enjoy the climb and views.

Back at the base, I took the bike and rode to Grimsel Pass via some iconic passes such as the Oberalp and Furka, a long but very nice ride. I arrived at Grimsel in the evening and it was quite chaotic as they were doing some work at the dam. But we finally found a good place to sleep and were able to rest for a few hours.

Stage 2: Bernesse Alps

Shortly before 5am, I left Grimsel pass and ran the loooooong Unteraargletscher moraine, a 20km glacier moraine. It’s not very difficult but progression wasn’t very fast in this terrain. I wasn’t feeling super fresh but not too tired either and I started climbing up towards Lauteraarhorn at a good pace. The uphill was very annoying with either very loose rock and sand or very soft snow. Every 2 steps I took up I was going down one. When I finally reached the summit ridge with more solid rock I started to be concerned about thunderstorms.

The forecast announced some lightning for the afternoon and it seemed it would arrive earlier than announced. I weighed the options: I could go down, find some kind of shelter or continue, knowing that once I started on the ridge towards Schreckhorn there wouldn’t be many places to hide. I opted for the latter and as I climbed I kept looking for options to throw away the metal gear and find cavities or shelter beneath the rocks to hide just in case. The thunderstorm was coming from the west and I could hear and see the lightning approaching fast. I wouldn’t say I wasn’t at all stressed but finally the lightning passed a few hundred metres from me and kept going east. After the thunderstorm, a snowfall came. So for the last part of the ridge to Schreckhorn it was pretty wet and snowy, but the rock was excellent and the climb was great so I could enjoy it knowing there wouldn’t be any more lightning. The ridge itself is very beautiful: excellent rock and pretty sustained with nice ambiance and views (when the clouds let me see anything). At the summit I was in the fog so it wasn’t easy to find a way down. It is pretty technical, especially lower down, climbing to the glacier. Once I was there, the sun came out and it became a very warm afternoon.

It wasn’t very easy to cross from Schreckhorn glacier to Finsteraarjoch. Long moraines, some climbing, and some crevasse navigation at the top. From there I took a long couloir up to Agassizjoch. It wasn’t very easy to cross the bergschrund with the ice from the last few weeks melting, but to the right side of the rock it was possible to join the couloir and climb up, half the way in the couloir in soft snow, and halfthe way on the rock. From there, the ridge to Finsteraarhorn was very loose rock at first until I reached the junction with the normal route. I got there by sunset, and just then another snowstorm arrived, making the last part to the summit very slippery.

The way down the glacier was OK. I could sometimes see some old tracks that made navigation easier. It was late at night when I reached Finteraarhorn hut, but the guardians were still waiting for me with nice warm veggie soup that I enjoyed before a couple of hours of sleep.

About 2 hours later, I put my wet shoes on again (urgh!) and started crossing the glacier towards Grunhornlücke, down east and up the normal route to Grunhorn, where I enjoyed an amazing sunrise. There, the snow and rain from the previous evening made the rock pretty slippery, so instead of following the ridge I went half-way down the west side glacier and crossed to Kleine Grunhornlücke. The ridge began with pretty bad rock but higher up it solidified, offering some very aesthetic climbing with a narrow long ridge to Hinter Fiescherhorn. That is where I saw the first people apart from the hut guardians since I’d left Grimsel pass. I quickly crossed to Gross and took the north ridge down and the long glacier plateau to Monchhute. After two days of solitude, seeing so many people was kind of a shock. I ate a bit there and went up and down Monch, a pretty busy mountain with some nice rock scrambling and a narrow snow ridge with great views of all the Bernese Alps. Crossing Jungfraujoch was pretty shocking with thousands(!) of people there in the glacier and the shopping centre that the station has turned into. After some hard navigation in the shopping centre tunnels I finally found the exit to Jungfrau glacier, left the noise behind, and went back to the quietness of the mountains for the rest of the day. There were lots of tracks up Jungfrau but it was late afternoon so the snow was very soft. The views from the top were amazing, with the green valleys to the north; Interlaken, Grindelwald… lots of memories came back from the two times I had been there before: in 2007 for a European skimo cup in Grindelwald and in 2015 when I joined Ueli Steck to climb the Eiger north face.

I took the way down to Jungfraufirn where there were some big crevasses and bridges to navigate to stay safe, then a long way down the glacier to Konkordia, where I went right up towards the north face of Aletschhorn. The plan was to climb the north spur and NE ridge, but when I was walking along the glacier up to the foot, it started to rain heavily. It would soon get dark and the long spur was taking lots of rain, making the rock wet. Besides, I was completely soaked and I wasn’t looking forward to the lower nighttime temperatures being that wet. So I decided to change plans and go down to the south face, hoping the rain would stop and that the SE or normal route would be a bit dryer. The way out of Aletsch glacier was insanely long. And to cross the glacier wasn’t as straightforward as I had thought with some big crevasses. At least the rising moon offered an incredible view. First I thought of staying on the right side of the glacier to go up via the NE ridge, but in the night I couldn’t find an easy way to exit the glacier. So I decided to not spend time and energy looking for a way there but instead to keep moving and go down to the end of the glacier and take the normal route up. That added a lot of distance but luckily the rain stopped and with all this movement, even during the night, my clothes dried a bit and I didn’t feel so cold.

The normal route to Alesch is a long way. After a long climb through the fields, a long balcony trail up and down, where I came across some wild and domesticated sheep in the dark, I reached Oberaletsch hut. I was pretty sleepy and tired, so I went into the boot room, lay on the floor, and set a 10-minute alarm. The guardian, who had just served breakfast for the climbers, saw me and offered me a bed, but those 10 minutes seemed enough. However, I gratefully accepted some breakfast. After the hut there were long leaders to the glacier and a long moraine to start the climb. I could see many lights in front of me and, despite feeling very tired and slow, I soon caught up with them. The climb there is very nice and varied. First some weird crossing over moraines and sand spurs to enter an easy scrambling spur, a short steep glacier section, and a long scrambling on a spur to the summit. I reached the summit just after sunrise and deeply enjoyed the warm touch of the sun on my skin. I could see just under me, to the north, the place where I’d stood 12 hours before in the rain. It was a long detour, but under those conditions I think it was the right call.

The way down was long as hell. Climbing down all that was almost as slow as climbing up, but after the cake and drink back at the hut I felt a bit more energised and was able to run down quickly to Bealp. A few kilometres before it, I meet Emelie and we ran together to the village where Maj and Ylva Li, our daughters, were waiting with the team.

I ate a bit –a lot– and took the bike for a short ride down the valley and up to Saas-Grund accompanied by Jordi Lorenzo. Emelie and the girls had been staying at Saas-Grund since Sierre-Zinal and it was nice to spend some time together before starting early the next morning. They would be going back home the next day.

Stage 3: Saas-Grund

Matheo Jacquemoud joined me early in the morning and we started hiking up to Weissmieshute accompanied by Nick Danielsson, one of the cameramen who was following the project. It had been a long time since we had been together with Matheo, but we had shared many moments together: the Aravis crossing, Mont Blanc, racing together Pierra Menta, Rutor… So it was nice to be together in the mountains after so long. Catching up about our families, his job at ENSA, athletes, and life in general. When we arrived at Weissmieshute and saw that the weather was so-so, we decided to go to Weissmies first.

The sun came up as we started crossing the glacier. Nick was waiting for us there and we soon passed the many people who were climbing above us and reached the summit. There I had a sandwich while Matheo prepared his wing. He paraglided down quickly enjoying perfect conditions, while I ran down the glacier to catch him at the bottom. We climbed to Lagginjoch and the south ridge of Lagginhorn, an easy but very nice and long ridge with amazing views of the Valais mountains on one side and the Italian plateau on the other. The normal Lagginhorn route is one of the easiest 4000m peaks to climb. All dry and with a trail, so the downhill was an easy run. Back at Saas-Grund I took the bike for a couple of kilometres to Saas-Fee. This day, with just 8 hours of activity, felt like a rest day and I could see how I could recover from the previous days’ efforts.

Stage 4: Valais

The forecast announced some snowfall for the next day so I was doubting whether to take a rest day, but finally I decided to go up to see how much snow was falling. After a long sleep, I set off at first light towards Mischabel hut, a very nice nid d’aigle hut in the mountain. The ascent is pretty direct, so I was soon on the glacier. I crossed it and climbed the ridge to Nadelhorn. During the night and morning around 15cm of snow had fallen. I felt like I was at home in Norway. Some wind, some snow, rocky ridges, and that feeling that when you see a centimetre of blue in the sky you can call it a sunny day! I climbed down Nadelgrat ridge to Dirruhorn and, since there was a lot of rockfall in the couloirs, I decided to climb back to Nadelhorn to stay safe. On the way down to Mischabel hut, I meet Ed Albrighi, a mountain guide and skyrunner who invited me to hot chocolate in the hut before we ran down together to Saas Fee.

The next morning Matheo came back and we started climbing the same way I did the day before to Mischabelhute. There we climbed the NE ridge to Lenzspitze. With the fresh snow and slippery rock the climbing was a bit delicate, but the rock was very solid and the moves were great, like dancing on the orange granite. We were waiting for the sun but it decided not to show up, and a deep fog enveloped us while we were climbing up Dom. Opening quite a deep track in the glacier, under these conditions, it seemed the day was going to be very long. From Dom, the ridge to Taschhorn is long, the rock is very poor at the beginning and the snow covered most of the route, so we decided to use the rope. It’s easy terrain but very exposed. We thought of Patrick Berhault who lost his life there in a cornice when attempting this vision. When the wind cleared the fog a bit, the views were majestic, like from another world with towers of black rock and clouds escaping from them.

After the lower point in the ridge, climbing towards Taschhorn, the rock becomes much better, offering some very aesthetic climbing on a narrow ridge. One of the best in the traverse.

The way down is an easy ridge to Mischabeljoch, and an easy climb to Alphubel, where we finally met the sun, and Genis Zapater with his friend Bryce. We went together to Allalihorn and there Bryce and Matheo went down. Matheo flew his glider and Bryce, David and Joel were there to film us. I continued with Genis down towards Allalinpass on a pretty bad rock ridge. We left some gear there and did a back and forth run to Rimpfischhorn. The night caught us when we started the rock climbing. Genis waited there and I climbed in the dark. Solid black rock, for once. Red sky showing the silhouettes of the mountains in the north –the pyramids of Matterhorn, Zinalrothorn and Weisshorn– and the full moon rising in the south over the Italian plateau.

Back at Allalinpass we went down north on the glacier to contour Rimpfischorn and up to Adlerpass, where Genis waited while I did a quick ascent at Strahlhorn in the light of the full moon. We then climbed down to the Adler, Findel and Gorner glaciers to the Monterossahute. Running down that last glacier, I tripped with my crampons and fell onto the ice. It was flat and hard black ice and with the things I had in my chest pocket (the GoPro, a GPS tracker), I injured one rib. I didn’t know if it was broken or just fractured, but that was not the first time it had happened so I wasn’t worried much about needing to stop. However, I knew that for the next two weeks it would hurt like hell when sleeping, doing far-reaching moves with the left arm, and when coughing. We had some info that we could cross the glacier pretty high to take some kind of via ferrata to enter the hut from above, but in the dark of night we couldn’t find it, so we ended up looping back in the moraine and taking the panorama trail to the hut where Joan and Andreu were waiting for us with some food.

After a couple of hours of sleep, I ate a good breakfast and at sunrise I set off for Monte Rosa. My expectations for the day were pretty wrong. I was expecting a day with plenty of tracks, making easy running trails in the glaciers, but soon reality told me otherwise. Up Nordend there were only a couple of people I soon passed and from there I was opening track. Same on the traverse from Duforpitze to Zumteinspitze. At Capana Margherita I stopped to eat and drink something. After a couple of days of seeing no-one, there were plenty of people on the summits here. The easy access and low technicality of those summits makes the area pretty popular. The route I followed that day is known as the Spaghetti tour because of its shape, starting from Monte Rosa hut and linking the 18 4000m summits until Breithorn. Most of them are very easy, just running on the glacier up and down. That day it was very hot and the snow was melting fast, making progression pretty slow and some holes opened up under my feet.

When I was doing the Lyskamm traverse, a very aesthetic and narrow snow ridge, I got a call from the Norwegian police. At first I thought something had happened to Emelie or the girls but my stress lowered a bit when they told me it was about my car, parked in an area where some work was about to start and it needed to be moved. After some calls and missed calls with the parking manager while I was running on the ridge back and forth, searching for a good signal to try and find a solution, the manager realised that my car could be opened and started via an app. So there I was on the ridge, trying to find a good signal to open and start my car parked in Norway, so the operator could drive it and park it elsewhere.

After that, I crossed Castore, remembering the multiple times I had been there training or racing Mezzalama and Pollux and went to Breithorn’s traverse. At that point I was very thirsty, hungry and tired. As I was passing Bivacco Rosi, a couple of alpinists making their dinner must have seen the state I was in. They offered me some of their boiled carrots and some water that felt like heaven. I continued with the traverse with the last light of day painting everything orange. There is some nice climbing there, never too hard but pretty cool and on good rock. On the downclimb it was a bit harder to find the best way to do it without abseiling. As night fell, I reached the west summit of Breithorn, my first 4000m peak, which I climbed when I was 6 years old with my sister and parents.

I ran down the Zermatt ski slopes to Theodulses lake and then crossed to Hornli hut. It was a long way in my tired state. Luckily, at the hut, Aina and my mom were still awake and I was able to eat some good food before a couple of hours of sleep.

I woke up before dawn and after a good breakfast I started climbing up Matterhorn. I started slow but soon felt good and quickly reached the summit. Conditions were great, not too much snow and, as usual, big tracks, but it was a windy morning. I thought it would be a busy morning on the mountain but I was pleasantly surprised to come across “only” a dozen teams on the mountain. At the summit I thought how cool it would be to have the fresh legs I’d had around the same date 11 years previously. The downhill on the Leone ridge was almost completely dry and went fast. At Carrel hut, the Cervinia guides offered me some food and I kept contouring Testa del Leone to start the long ridge towards Dent d’Herens.

In 2017, we did this ridge together with François Cazzanelli, when we linked the Grandes and Pettites Murailles and I had some memories of the route, never too technical, but some climbing in very poor rock. The climb went well, it offers some great climbing and it’s a long ridge with multiple gendarmes, all of them with different characteristics of rock and formations that makes the route very varied. I was surprised to see some foot tracks every now and then along the route. It’s not a very common route to climb. Afterwards, I found out that I was the 3rd person or team to climb it that year, just after Rolf Zurbrugg and his client. I know Rolf from when he was the coach of the Swiss skimo team and it was a pleasure to meet him there at Rifugio Aosta after the climb. We chatted for some time about old and new times while enjoying some food and I set off for Cole della Divisione before it was too late.

Before the pass I met Genis and Bryce, who came to join me for the Tête Blanche glacier traverse. Last time I did this glacier crossing, back in 2015, it was also in the late afternoon on a very hot day. The snow was soft and it took me hours to cross. I almost fell into some crevasses and “swam” over them to spread my weight and prevent the snow bridges from collapsing. This time it was much better. The snow was hard and the progression fast. We enjoyed another great sunset when we arrived at Cabanne de la Dent Blanche just for dinner, where the guardian, George, had prepared a delicious risotto with mushrooms and parmesan. After dinner, with Matheo, who had climbed with his friend Noa to the hut, and Genis, we continued to the summit of Dent Blanche. The ridge there is just beautiful. Perfect solid rock, some nice climbing, but never hard. I had done that route a few times, with Emelie and alone, but this time I was surprised how little snow –well literally not any– was on the ridge. The full moon helped us see the route better and gave us an amazing night view of all the Valais mountains.

We downclimbed the same route and Noa went back to the hut while Matheo, Genis and I kept climbing down in a steep spur towards the Schonbiel glacier and then crossed to Schonbielhute, in the early morning, where Joan and Andreu had made some sandwiches for us.

We slept one hour and with Matheo we kept running down the valley and then up to Arbenbiwak. The views there were astonishing. The sun was rising and lighting up the north face of Matterhorn behind our backs. We saw a couple of Alpine ibexes and some people in the ridge above us. The Arbengrat ridge at Ober Gabelhorn is one of the classic Alpine ridges for good reason. Perfect orange rock for the most part, sustained easy climbing with amazing ambiance for pretty long to the small pyramid of a summit. We had some food at the top while enjoying the views before we started climbing down the north ridge, first with some steep rock and then some snow and ice up to Wellenkuppe. The traverse there is a very complete route, with lots of variation between rock and snow climbing.

At Rothornhutte, Matheo went down to Zermatt and I carried on towards Zinalrothorn, another great rock route very similar to Arbengrat with some nice climbing to the narrow top. The downhill in the north also offers some equally nice climbing. It was a pleasant surprise to meet a familiar face there, Bjørn Kruse, a mountain guide from Romsdal with whom I had been skiing and climbing and had written a steep skiing book about our home mountains.

When I reached L’Epaule I started to check the time of day. The ridge from there to Weisshorn is very long and not easy. In 2015, I did it in the opposite direction and I remembered several abseils, some technical downclimbing and a full gendarme of rock that collapsed a few minutes after we climbed down it. I saw I had about 5 hours till sunset and I wanted to have passed the difficult parts of the south ridge of Weisshorn when night fell. First there are the two Morming summits, never too hard but with very poor rock and quite aerial. After that, a steep way up on ice to Schalihorn followed by a long ridge with multiple gendarmes to Schalijoch, where there is a small bivouac hut. I felt good, maybe because of the adrenaline, but I soon reached the bivouac and felt somewhat relieved to have a couple of hours to climb the south ridge before nightfall. At the bivi there was a team from Germany cooking and preparing for climbing the next day. We exchanged a few words but I wasted little time before starting to climb that magnificent ridge.

Weisshorn is one of my favourite Alpine mountains. There’s no very easy way up to the summit, even if it’s eclipsed by its neighbour Matterhorn. Its shape is a perfect pyramid with long ridges on all sides. The south ridge is a long climb, almost 800 m of ridge on very solid rock. It’s not very sustained but it has some steep parts that require some real climbing. What I experienced there will remain with me all my life. I felt effortless, like I was floating in a cloud as I climbed up the ridge. The sun setting in the west and the clouds in the east gave me the gift of a broken spectrum following me all the climb, replicating all my movements in the sky. At some point I couldn’t tell if I was really there or if it was a dream.

I reached the summit before the sun went down and, after enjoying one of the craziest sunsets I’ve ever seen, I started downclimbing the north ridge. That ridge is no joke. Although it’s way shorter than the south ridge, it involves several gendarmes, some narrow ice ridges and some steep rock climbing. Since I was starting to feel tired –I’d been climbing for more than 40 hours with very little sleep– I decided to abseil down the steepest gendarme instead of climbing down the ridge. In the past I had always climbed down and followed the ridge but I knew it was possible to abseil lower down and traverse on some ledges under the ridge. That was a bad decision. Either the dark of night stopped me from finding the best way or those ledges were just on very, very poor rock. Anyway, I needed to focus all my attention on not bringing the whole mountain down with me. After some careful hours there I was finally able to relax and climb up Bishorn and down to Cabane Tracuit, where the guardians had prepared some nice warm food. After eating a bit we ran down with Nick, who had come to film there, to Zinal. A week after I finished the race, I was back there, much slower and tired, but very happy to have completed the Valais couronne.

Stage 5: Grand Combin

After a long sleep –well, at that point 5 hours felt like I had overslept– I took my bike and went down the route I’ve done many times with the bus to the start of Sierre Zinal. I cycled then at turtle speed to Martigny and started to feel more energised cycling up to Bourg St. Piere, where I meet the team and regained some energy with a good lunch while waiting for Alan Tissieres.

I knew Alan from his early years in skimo. He was one of the most talented young athletes and we had some great times – mostly partying together in the after-race parties. That morning Alan was guiding at Dent Blanche but he decided to come and join me anyway to climb “his” mountain, the Grand Combin, since he was born and has been living at its foot ever since then. It was more than 10 years since we had seen each other and he was now working as a mountain guide, far from the competitions but still in great shape. I felt good after the long sleep and the easy ride and we went quickly to Cabane de Valsorey, where Alan’s cousin, the guardian, offered us something to drink. After some discussion with her about why we were not wearing helmets –Alan concluded that a helmet couldn’t do much in the event of a rockfall– we continued up to the pass where the Meitin ridge starts. More than a ridge, the route is a zigzag route on a big rocky face. It has pretty solid rock if you don’t lose your way, but very poor rock if you do. And believe me, it’s pretty easy to lose your way there. The climb itself is not sustained at all. There’s a lot of walking or easy scrambling followed by a few metres of some climbing. It carries on like that for about 500 metres. We got to enjoy another –yes, another– amazing sunset as we were reaching the first Combin, Combin de Valsorey. To the west, the sun was setting behind the Mont Blanc range, and to the south, a thunderstorm was lighting up the Italian plateau. At the summit we used the rope and headlamps and followed the snowy ridge to Grand Combin, Aiguille du croissant and Combin de Tsessette, before coming back, cutting under Grand Combin to the first summit and climbing down the ridge back to the hut, where Alan took out a couple of pieces of cake and we enjoyed eating them in the silence of a starry night.

Alan stayed there to sleep and I continued down to the village, not without some encouragement from the guardians, who were sleeping outside the hut under the stars.

The next morning, I took my bike and rode to the next valley. There Jules-Henri Gabioud was doing his final training before racing PTL at the weekend. When he passed me, I joined him for the last kilometre to La Fouly. He told me it was better to take Petit Col Ferret to cross to Italy instead of the Grand Col, since the latter would be full of runners. So after wishing him all the best for his race, I left the bike and hiked/ran up the pass and down to the Italian side of Val Ferret to the Jorasses campsite, where the team was waiting.

At the campsite, after eating and resting a bit, I double-checked the weather forecast. A storm and some snow were predicted for the following day. Since the next stage was going to be pretty hard both physically and technically, and starting with a bad weather day might compromise the feasibility of the climbs, I decided to take a rest day and start at midnight after some quality rest.

Stage 6: Mont Blanc

Michel Lane, a longtime friend who works at PGHM, who shared team and trail running races with me for a long time, came with Bastien, a friend from PGHM, to join me for the day. Matheo also came and after midnight the 4 of us started hiking up from Val Ferret towards Rifugio Boccalatte. We were moving pretty quickly, without forcing it but without stopping. Before sunrise we had reached the summit of pointe Walker in perfect hard snow condition. It was a clear and pretty cold night, so we didn’t stop long and continued to the west traversing Grandes Jorasses. I had done this traverse in the past in the opposite direction and I thought that east to west wouldn’t be as nice, but I was surprised how logical and nice it felt. There was not so much abseiling (only after Pointe Young) and climbing the gendarmes in this direction offered some nice climbing on good rock. The views and aesthetics of this ridge are unique. The history of the climbs on the north face of Jorasses is something you’re very aware of when you’re up there. It was quite a cold day so we kept moving all the time and we were very happy when the sun touched us when we reached Poine Young. The four of us carried on at a good pace to Rochefort, where we meet Noa. With him and Matheo we went to climb Dent du Geant while Mitch and Bastien went directly to Torino hut. Dent du Geant is such a beautiful needle in the skyline of the Mont Blanc range. A unique summit that offers some of the best granite one can imagine. Despite the number of crags in the wall, some fixed ropes destroy the feeling of mountaineering there a bit. Anyway, it wasn’t long until we summited and joined our friends at Torino hut for some snacks and drinks. There we called Tom Lafaille, who had gone down Mer de Glace a week before to ask about the conditions of the glacier crossing. While Mitch, Bastien, Matheo and Noa remained at Torino, I went down the Vallée Blanche towards Refuge du Requin, not without some crevasse navigation to exit the glacier, and then up to Refuge du Couvercle.

I got there pretty “early”, so I had time to rest a bit and enjoy dinner with the other climbers and guardians for once. It was a great surprise to see Simon Elias there. We had climbed Colton McIntyre together on Jorasses north face in 2015. Now he combines his work as a mountain guide with searching for rock crystals in the mountains. That takes him to the rottenest walls of the mountain range, where these precious crystals form. That’s basically why he is spending the summer in this hut. We discussed the conditions a bit and since they were very bad –“Everything is collapsing up there,” he said– we considered the best route to minimise risks.

I woke up at four and after some breakfast I set out from the hut, contouring Aiguille du Moine. Physically I felt good but my body was tired. I knew that the risks I would be taking that day would be high. It felt a bit like I was going to the slaughterhouse. I crossed the bergschrund at first light and started climbing the Arête du Moine towards Aiguille Verte. The arête I remembered didn’t exist anymore. The multiple rock falls and collapses had changed its shape and it had become a pretty unstable route. I met Simon half-way up, where he had some tools and gear. It looked like it might collapse any day. I continued up to the summit of Aiguille Verte. I had been there a few times before, all in winter with my skis, and I must admit that it’s a much nicer summit in winter, when the snow and ice keep it all together. The summit of Verte is spectacular. Set back a bit from the main range, it offers a unique perspective, with the north face of Jorasses in front, the Argentière basin on one side and Mer de Glace with Aiguilles de Chamonix and Mont Blanc on the other. There aren’t any very easy routes to the summit, which is why the legendary alpinist Gaston Rébuffat said “Avant la Verte on est alpiniste, à la Verte on devient Montagnard”.

From the summit, a narrow snow ridge took me to the summit of Grande Rocheuse. From there, the downhill and climb to Aiguille du Jardin started to show how the day would play out. Staying on the ridge, the rock was OKish, but when I needed to go to one side or the other, it felt like I was playing Jenga with the rocks. Aiguille du Jardin is a very nice tower and the views are pretty incredible, but my mind was on what was coming. That was probably the last place I could decide to turn around and get down somewhat safely. I decided to continue. The descent from there didn’t feel good. I did some abseils in poor bequets and old slings. A large part of the wall that I abseiled had collapsed not long before. I could see the permafrost exposed to the sun, with large blocks, the size of a car, remaining, which I abseiled down. I tried to go as fast as possible, abseiling and downclimbing, to avoid exposure to that as much as possible. A bit more to my right, every now and then, some big blocks of rock were collapsing taking big rock avalanches with them.

After some time where I think I grew some grey hair, I arrived at Col de la Verte. There the solidity of the rocks wasn’t better, but at least I was on the ridge so things from above couldn’t fall on me. The terrain was basically sand. Sand sticking together for the moment. I downclimbed south to contour some needles and climbed back again to the ridge as quickly as I could. The Droites ridges started there. Not very technical at the beginning, but with some hard moves higher up, where I stayed on the ridge itself to avoid climbing on the sides. Once, when crossing a gendarme climbing on the north side, all the rocks under my feet and hands –except one hand– collapsed and fell down a few hundred metres onto the Argentière glacier. I clung on with one hand, hoping the rock I was holding would stay in the wall for a bit longer.

I’m not someone who stresses much in general. I think that gives me an advantage on most occasions when racing or doing projects like this where concentration and keeping calm all the time is key. But that was one of the few times I’ve felt a knot in my stomach for hours. I really didn’t know if I was going to make it.

When I reached the summit of Droites I didn’t really enjoy it and just started to find the best way down. Col des Droites seemed to be covered with snow and the safest way, but on the way there the couloir was a bowling alley. I decided to downclimb the spur and try to cross to the snow fields from Col des Droites when I found an opportunity. The downhill was somehow OK when I stayed on the very edge, and after a few hundred metres I found a possible traverse to cross that bowling alley and reach the snow. I felt safe for the first time in hours. I felt that today I wasn’t going to die. While climbing down and traversing back to Couvercle I didn’t feel happy or sad. It was a strange feeling, not being well with myself and the decision I took to continue that day. I mean, the small decisions of where to abseil, where to pass, how to downclimb or how to protect myself had been good and that’s what kept me alive, but the decision at the first summit to keep going was something I wasn’t happy about.

I arrived at the hut exhausted mentally. I discussed it a bit with the guardian and ate something. Then I kept going down to Mer de Glace and up, following my tracks from the previous day, towards Torino hut. When I entered the glacier after Requin it started to rain.

I reached Torino in the early evening. There was Jordi Tosas, a good friend who was guiding there, Matheo and Noa, and Aina and my mother. I ate a great and copious dinner and had a good sleep, trying to clear my mind.

The next day, Jordi joined us for a few minutes before running back to his clients at the hut. Matheo and I carried on in silence, crossing the glacier around Grand Capucin in the dark. When we turned the corner we saw Noa’s headlamp; he had started a bit earlier to film us. The bergschrund to climb Col du Diable was pretty steep. We made a pedal with an ice screw and a sling and we passed one another a second ice axe to climb the steep 5 metres of ice. We then continued on pretty poor rock –it felt like marble compared to the previous day– to the Col. There the sun started to rise, giving us a breathtaking show of colours and views. While Matheo started climbing towards Pointe Chaubert, I did a quick back and forth to Corne du Diable and then the three of us climbed this magnificent ridge together. The climbing there is really, really great rock –the famous Chamoniard orange granite– and every one of the gendarmes offers some athletic movements and perfect crags to climb. It is definitely one of the best rock climbs one can do in the area, in terms of the quality of the rock, the beauty of the moves and the incredible views and surroundings. I really enjoyed that climb although we moved quickly we took the time to savour it. 6 hours after leaving the hut we reached Mont Blanc du Tacul, where we met David and Nick who went there to film us. We chatted a bit and continued towards Mont Maudit. There weren’t many people on the mountain that day, just a couple of teams going to Mont Blanc. We stood alone on the summit of Mont Blanc, where I left the rope and some warm clothes I might need for the second part of the day and we ran down the normal route to Dome du Gouter and then to Aiguille de Bionnassay.

I’ve done this summit several times in the past and I always remember it as this perfect narrow snow ridge. This time I was surprised to see that the ridge now had some long rock sections. Nevertheless, it is still one of the most aesthetic ridges one can imagine. Matheo and Noa continued down from there, while I turned around to climb back to Mont Blanc. It’s a long climb, almost a vertical kilometre, but I felt pretty good and it wasn’t long until I was back on top of the Alps.

I picked up the rope and clothes again and started going down the south side of the mountain. There were some old tracks that gave me hope I would found some tracks lower down to cross the glaciers. When I started climbing down Brouillard ridge I meet a team of climbers who were finishing the integrale du Brouillard. I asked about the conditions and it seemed it was pretty dry, which was perfect for downclimbing. Soon after Pico Luigi Amedeo I took off the crampons. The ridge is never too technical but has some steps up to 4 degrees, so downclimbing can be a bit delicate. I was enjoying a perfect sunset with the ridge half in the sun and half in the fog, living up to its name. The steep section to Col Emile Rey went smoothly. Mostly downclimbing, with a short abseil.

Night fell at the Col. I took my headlamp and left my backpack. I followed the ridge pretty quickly to Punta Baretti and back. Sometimes it was pretty foggy and at night I used the trackback function so as not to lose my way back to the col. There I climbed down the snow couloir to Glacier du Brouillard. It felt all surprisingly easy and smooth until this point.

As I crossed the glacier, I noticed some rock fall from the Brouillard face and the right branch of Col Emile Rey. When I started to climb towards Col d’Eccles, I found a huge crevasse all along the length of the glacier. I looked around a bit but couldn’t find an easy way to cross it. Shit! After thinking a while, I went back to see if it was possible to climb down/abseil Glacier du Brouillard to contour the rocks and climb to Eccles bivouac by the normal route, but the glacier was pretty rotten and I couldn’t find any reasonable way.

A bit disappointed, I thought that the only reasonable solution would be to climb back up Col Emile Rey and climb down Integrale du Brouillard to Val Veny and the next day climb up the normal route to Eccles and to Freney.

When I crossed the glacier back towards the Emile Rey couloir, a big rockfall came from the top. I couldn’t see much but heard the rocks hitting the wall and the huge sound of a mountain falling above me. I ran to cover myself as well as I could on the open glacier and a few seconds later, in the beam of my headlamp, I saw rocks the size of basketballs flying through the air. After a few seconds of chaos, the noise quietened down and a thick cloud of sand and dust covered me for the next ten minutes. Well that was a close call! No way was I going to climb back up there so I needed to find a solution in that crevasse.

I crossed back and found a snow bridge in the crevasse that could lead me to the other wall. I then climbed the five or so metres with the ice axe in one hand and an ice screw in the other to progress. It was slow but safe. After some searching I found a way up the rock to climb to Eccles bivouac and entered the shelter pretty done emotionally. Better to call it a day, rest a bit and wait for some light to see where the rocks were falling from before continuing.

I ate the rest of the food and drank the water I had with me. I took off my wet shoes and socks and covered myself with the three blankets I found. I slept like an angel. Three hours later I woke up and waited for daylight to come. I left the bivouac and climbed Pic d’Eccles. The sunrise offered me one of the best views I’ve ever enjoyed, with the light entering from Col du Peuterey between the two summits I was going to climb and behind, Verte, Droites, Dent du Geant and Jorasses where I had climbed the previous days felt far away.

I did a short abseil to the pass with the remaining rope I had –the rope had been cut many times over the last days with rockfalls in Droites and Brouillard– and climbed down a dry couloir to Freney glacier. Conditions were perfect on the glacier with hard snow and no transversal crevasses so I reached Col de Peuterey in no time. There I first went towards Grand Pilier d’Ange, climbing well on the right ridge to avoid being exposed to the constant rockfall from the central part of the wall. The climb there is a bit more technical but way safer.

After some time I reached the summit. I saw and took with me some (very) old pieces of ropes I thought they could help me with the abseils in Aiguille Blanche and downclimbed to the pass, leaving a piece of rope to cross the bergschrund. I climbed Aigulle Blanche, one of the most beautiful summits in the area, and at the summit I saw a team coming from the south, probably doing Peuterey ridge. I stayed at the summit of Blanche for a while, enjoying the views and the luck I had to be there, in such a beautiful place doing what I love doing. Then I climbed/abseiled down with the short ropes I had and crossed back to Col d’Eccles, the bivi and down towards Monzino. At the hut I ate and drank a bit, it was more than 10 hours since my last drop of water or food. Then I went quickly to Camping della Sorgente, where Matteo Pellin and his family welcomed me in the best possible way.

With all the team reunited there, it felt like all the difficulties of the project were done. That from there on it was just a matter of physical effort to do the last 3 summits. I was able to rest well, take a shower and eat plenty to regenerate body and mind.

Stage 7: Grand Paradiso

Right at sunrise, I was joined by Vivian Bruchez, who introduced me to steep skiing more than a decade ago and has been doing the incredible project of skiing all 82 4000ers in the Alps over the past decades, and Matheo Jacquemoud. We took a nice –social– bike ride to Pont. Half-way along Henri Aymonod, a young, strong mountain runner from Val di Rhemes joined us and we kept chatting about life until we reached Pont.

There Viv turned back –he was injured so he couldn’t climb by bike– and Emily Harrop, a ski mountaineering world champion, joined us to climb Grand Paradiso. I felt very well that day. I don’t know if it was the long sleep, the amount of food or getting over the most cognitively demanding journeys, but I was able to go up pretty fast and easily. With Henri we reached the top and ran down –with a short stop at Vitorio Emmanuele hut for a crostata– to Pont in what it felt like a recovery run. I ate a lot while waiting for Matheo and Emily, and Henri drove off for a race he had the next day, where he finished third in a very strong field!

I then ran a very nice trail up to Colle del Nivolet and Col de la Loze and down to Le Fornet, close to Val d’Isère, where the team was waiting for me and we were able to have a long 7-hour sleep!

Stage 8: Ecrins

At sunrise I started riding up Col de l’Iseran. I had done this pass multiple times, cycling when I was young and roll skiing when we were doing the summer stages at Tignes with the skimo national team. It’s a very nice pass, with great views over this part of the Alps with plenty of glaciers and green fields. Afterwards, I climbed Col du Mont Cenis, which has an incredibly beautiful large lake at the top and went a long way down to Susa, where the temperatures were crazy hot.

I climbed to Montgenevre and down to Briançon. I felt like I was in a cloud. I was treading easy, just enjoying the fact that it would be the last day of an incredible journey that took me physically from 1000 kilometres in the east to here, and emotionally to places I had never been before.

At Vallouise, Leo Viret, an old friend from the skimo years, and now the coach of many of the best skimo athletes and alpinists, joined me for the last kilometres. We discussed physiology, training philosophies and lifestyle. I arrived at Pré Madamme Carle a bit after four. Matheo was coming from Chamonix and would arrive later, so I waited while eating and talking with Aina and my mom about what had happened over the last few weeks. “It’s not done yet… but it felt so close…”

Just after five, Matheo arrived and shortly after Benjamin Vedrines, one of the best alpinists of this generation who had just come back from K2, joined too. We started walking up towards Glacier Blanc. Neither fast nor slow, chatting. About projects and life, about everything and nothing. When we reached the glacier, we started jogging. It felt good to be moving after so many days. Twenty years ago, I ran on this glacier to do my first FKT, bettering Jean Pellissier’s time up Dome de Neige. A decade later Matheo bettered my time. It was nice to be running there together, and with Benj, who is leading the next generation of technical and fast alpinists.

The sunset caught us under the summit of Dôme. Red mountains in the north. There were some crevasses to navigate but the route was pretty smooth. After Dôme we followed the rocky ridge to Barre des Ecrins. A hug, short and deep. A few words, some laughs and a muffin that Benj carried in his backpack. It was quiet, there in the dark, with the silence of the night broken by our words, but it was beautiful.

We climbed down the ridge and the glacier. A couple of climbers that were doing a bivi in the glacier welcomed us naked, celebrating our journey. On the way down Benj twisted his ankle –I wish him a fast recovery for the amazing projects he has planned– and before midnight we arrived at Pré, where Aina, Nuria, David, Joel, Nick and Joan were waiting for us. We didn’t say much; it wasn’t necessary. We ate a bit and went to sleep.

What I’ve learned

It will take some time to assess and assimilate such a journey, but here some thoughts on what I’ve learned.

I think I managed this traverse very well physically. My weight was stable all the time. While in the Pyrenees I lost weight and was constantly weakening, here I might lose a couple of kilos during a long stage but recover them quickly in easier stages. At Sierre Zinal I weighed 54kg and after the last stage in Ecrins I was also 54kg. Besides that, even if I lost power and speed, I was able to keep a decent constant pace all the way along. The last two days at Grand Paradisso and Ecrins showed that metabolically I hadn’t lost much. When it comes to pain etc., my hands were pretty OK. I think that is due to arriving very healthy/in shape at the start of the project (see my training this year) and the fuelling strategy during the traverse, based on following circadian rhythms, not eating often during the day but large quantities and, when I was down in between the mountains, eating some food I could absorb well (anti-inflammatory, managing acidity, increasing protein, fats, etc.). And hydrating, as when I was in the mountains I couldn’t drink much (basically about 1L per day when I was climbing).

It was a great help to have Jesús and Sergi giving me tips on the best nutrients (macro and micro) to recover from day to day and be able to absorb the quantity of nutrients and energy I needed. So nutrition management, not only calories in/out but the nutrients necessary to absorb those calories and to restore systemic functions during such long-term projects is key. When we have analysed all the data collected during the project we will be able to draw clearer conclusions about the internal processes that happen during these kinds of efforts.

I climbed most of the time with gloves and that saved most of my skin. Although I had some hard points under my feet or where the crampons were, my feet were OK. My rib and left extensor retinaculum were sore due to accidents. It was interesting to see that my rib was pretty painful for the next 2-3 days after breaking it, especially when doing some opposing movements while climbing, but then the pain faded completely, until after I finished, back home, the pain came back at high intensity for two more weeks. This was probably due to the neural signal management/avoidance during a period of time when my routine involved many hours and movements where the rib was mobilised. It was interesting to see how, in different situations, we can hormonally and neurally adapt to manage such situations, both in the short term (for example when during a fall, avalanche or rockfall adrenaline levels give us a boost in energy), the medium term (e.g. during unavailability of energy intake in a situation of risk, we are able to keep going at different intensities for a day or so until we reach a safety situation) and the long term (how the neural pain signal from a broken bone is eliminated for several weeks in a situation where the bone is mobilised continually, until the situation ends).

It was also very interesting to see how the hormonal response in dangerous situations could provide an energy boost in intensity and duration. The release of hormones such as adrenaline, cortisol, etc. in situations where I needed to keep going without any food, to go faster than I was able in the previous minutes/hours or to do a movement that required more strength than I believed I had, was very noticeable. Entering fight-or-fight mode was equally interesting on the physiological and cognitive spectrum.

I think the most difficult part of a traverse like this is to keep alert and concentrate for such a long time, knowing that conditions will be challenging at times. The physical toll is one thing (that hopefully we can soon determine with the data we collected), but emotional and cognitive fatigue is, in my opinion, bigger.

Comparing the effort with other projects I’ve done, I would say that the biggest difference was the continuous concentration. When I did the Pyrenees project last year, physically I finished much more tired. I think this was due to a worse approach to fuelling and “resting”. But the mental toll was lower as the only danger was my possible technical fault. On an expedition in the Himalayas, trying a difficult route, the amount of mental stress is high but often concentrated in the few days of the push, since there’s a lot of rest in between the pushes. On this traverse, since the route was mostly staying day and night up in the ridges to link peaks, I had to stay alert to dangers most of the time, as they were internal (technical fault, neuromuscular fatigue, etc.) or external (crevasses, seracs, rock falls, rock collapses, etc.).

Link-ups in mountains have been done since the beginnings of alpinism. And with the evolution of gear, physical and technical capacities, as well as knowledge of strategies and logistics, the possibilities for longer or faster link-ups have been increasing exponentially. One great example was when Ueli took his paraglider to get down from some summits during his link-up. This strategy evolved enormously this spring and early summer, when para-alpinists Peter Von Kanel and Chrigel Maurer linked all the 82 4000ers in 51 days, using their paragliders not only to get down from the summits but to climb them or travel the great distances from range to range, opening up a world of new possibilities for para-alpinism in the future.

I think that the fact that I took 19 days to climb the 82 4000m peaks in the Alps, compared with the previous link-ups by Franz and Diego or Ueli in 60 and 62 days is not due to the improvement in physical capacities but to a different approach to linking the summits.

When we look at previous link-ups we see mostly “short” link-ups (from several hours to a 3-4-day push) performed as a non-stop push where several summits/faces were climbed in a push with no or short stops; or “long” link ups (a push of more than 1.5/2 weeks) with multiple summits/faces where the strategy was to climb a summit; or a “classic” one-day link-up, going down to the base afterwards, getting some rest and climbing another summit.

This project answered the question by merging the two approaches. Doing a “single push” style in a long link-up. The physical questions were one part. How many hours can we push before we need to rest? How long should that rest be? And how can we manage the energy intakes for it? The second part was conditions management. When we do a “short” link-up we often wait for a good weather forecast and the best conditions to start and it’s somewhat “easy” to schedule the timings to go through certain sections when conditions such as temperature, rock stability, snow hardness, etc. are good. When doing a long single push, it’s impossible to predict weather for so long and at some point also to manage where you will find good conditions for progression and safety. So how to manage bad weather, bad conditions, was in my opinion key to success in a long push. In the end, that involved leaving a lot of room for improvisation, having knowledge of techniques and strategies to stay safe when those conditions arrive, and then to manage the resulting stress.

My last question concerns that final point : how do you keep alert and concentrate when doing high-stress activities for hours on end with fatigue and sleep deprivation day after day. On the one hand, you need experience of doing high-stress activities (climbing solo, on bad rock, at night, in bad weather, etc.) for a long time, so when you face it you don’t need to think too much to make a decision. It is automatic based on past experience. And on the other side, there’s your temperament; being able to return to calm and baseline stress/relaxation levels after high stress situations is key to reducing the cognitive and energetic load from it.

A long time ago, during my first experience in the Himalayas, in the lodge drinking tea while winter was bringing more snow to the mountains we wanted to climb, I was listening attentively to my companions. They both had extensive experience in technical mountaineering and high altitude. I remember Coro saying that “alpinism” was that day when you come back home and you can’t describe what you’ve done. “Have I been climbing? Yes, but that’s not what made it special… Have I been sleeping outside in the snow? Yes, but it is not about that … Have I been walking on exposed terrain getting physically exhausted? Yes, but it is not that…” Maybe, just maybe, alpinism is using the tools and knowledge you have built up over the years to solve the problems the mountain presents in different forms. In this project, the numbers don’t mean anything. The highest graded technical route in the traverse was a 5c, but there was good rock there, a common route where navigation did not come into the equation. Many easier graded routes felt much more technical, a IV grade in sand, or in a snowstorm, can easily became much more complicated. In this traverse, I didn’t do any new routes, I didn’t do any hard climbing, but in the end it was difficult to describe what it was. In the end that is what is beautiful: feeling what it is without being able to describe it because there are no measures and tags that can explain the deepest emotions.

Some random data

While we wait we can process the data we took to analyse the effects of such an effort on the metabolism, and the epigenetic, physiological, microbiota and cognitive impact. Here are some very random useless data:

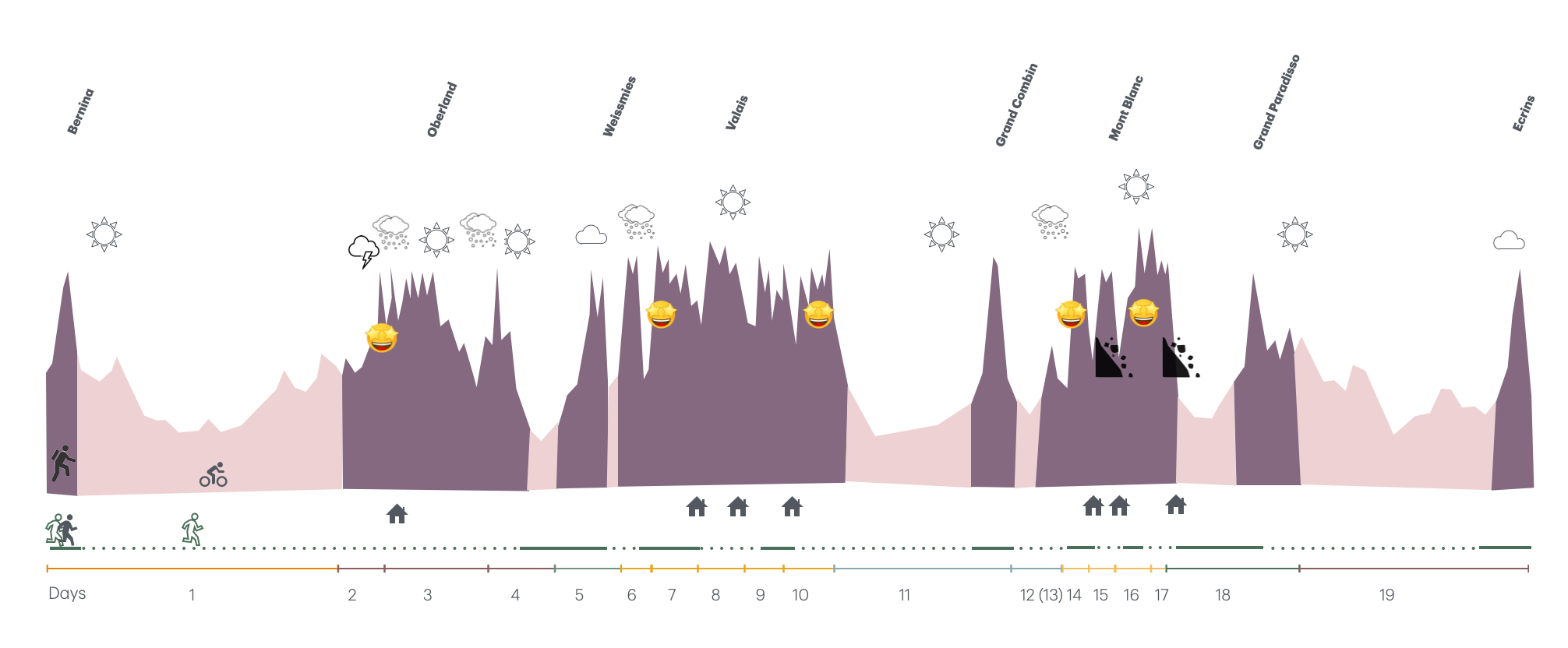

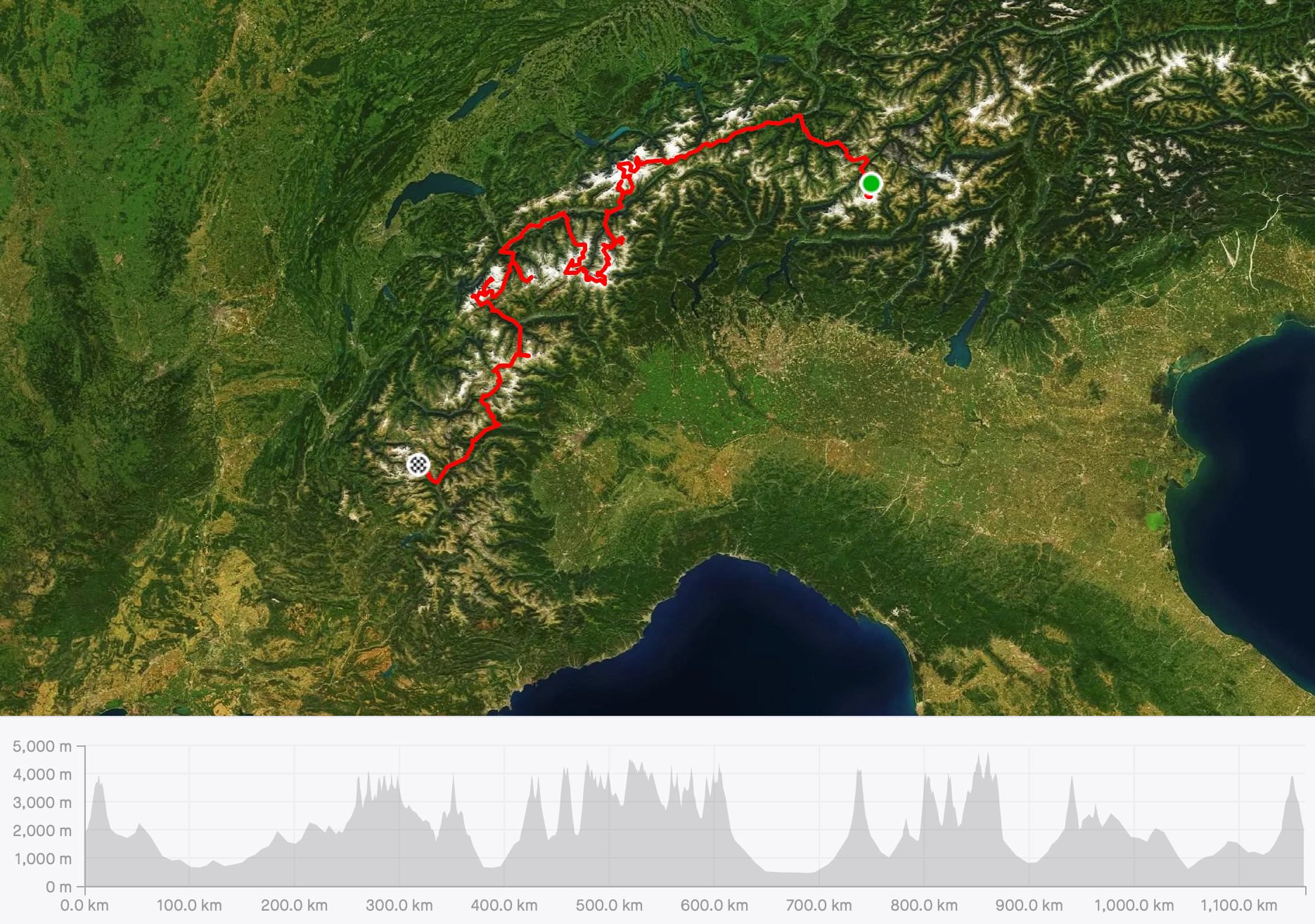

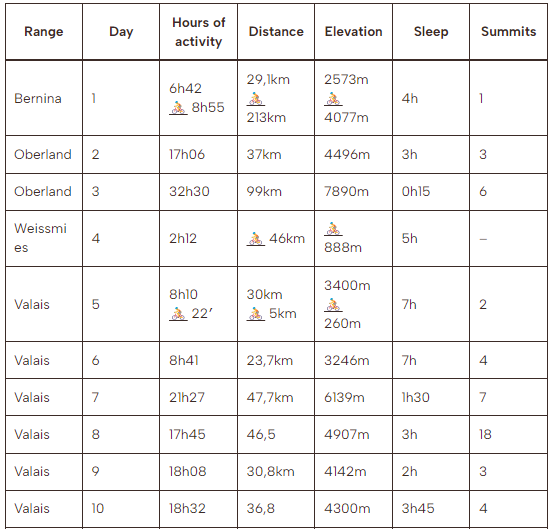

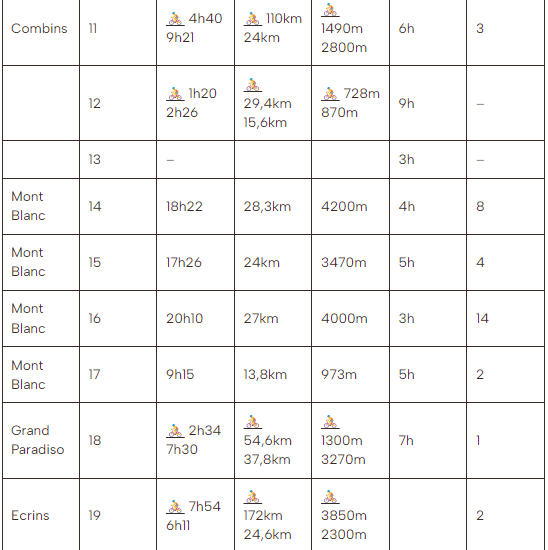

Profile with mountain ranges, weather conditions, favorite climbs, rock falls, climbing/walking and bike sections, huts where I slept, sections done accompanied and alone, and days on the journey.

- Weight of the pack: most of the time in the mountains my pack weighed between 4 and 7kg

- I did 34 summits accompanied and 48 alone.

- My shortest sleep was 15 minutes and the longest was 7 hours.

- Matheo followed me the most, completing 30 summits himself!

- The most common food for me in the mountains was sandwiches with avocado, oil and fresh cheese, or some homemade “cocoa cream” with beans, cocoa, nuts and coconut oil.

- I spent an average of 8300cal/day (analysed with doubly labelled water for the first 7 days).

- I enjoyed 12 beautiful sunsets and 11 amazing sunrises while climbing.

- I didn’t see anyone on 2 days.

- The summits I met the most people on were Aletschhorn, Monte Rosa, Matterhorn and Gran Paradiso.

- The most “enlightening” moment was climbing up Weisshorn, with the sunset, the broken spectrum, and feeling like I was floating up.

- One of the things I drank the most to recover was oregano infusion with coconut oil and beetroot, ginger and curcuma smoothie.

- The night I slept the best was at Eccles bivi, only for 3 hours but very deeply.

- I used 4 pairs of gloves during the crossing. All of them were completely worn, with holes in all the fingers.

- I climbed up or down more than 160 different routes during the trip. Some were nice, some very nice and some not so much. The ones I enjoyed the most, for their rock quality, ambiance and/or aesthetics were the Lauteraarhorn-Schreckhorn traverse, Dom-Täschhorn, Rimpfischhorn, the east ridge at Dent d’Herens, Arbengrat at Ober Gabelhorn, Rothorngrat at Zinalrothorn, Schaligrat at Weisshorn, Jorasses-Rochefort, Aiguilles du Diable, and Arête du Brouillard.